26 Apr It’s All About Inflation

As we write our quarterly recap the U.S. Labor Department has released its monthly report of inflation, and it’s a doozy. The consumer price index jumped 1.2% in a month and is up 8.5% from a year ago, the largest increase since 1981. Gasoline accounted for half of the montly increase and food was the next largest contributor. Excluding those volatile elements, core inflation was still up 6.5% from a year ago, which slightly exceeds the 5.9% year-over-year gain in workers’ wages. The Fed has (belatedly) joined the inflation fight in earnest. It has signaled a 0.50% increase in the federal funds rate at its next meeting in early May and also expects to begin trimming its massive bond portfolio. Unsurprisingly, interest rates have shot up with the 10-year Treasury recently surging to 2.7% from 1.5% at the beginning of the year.

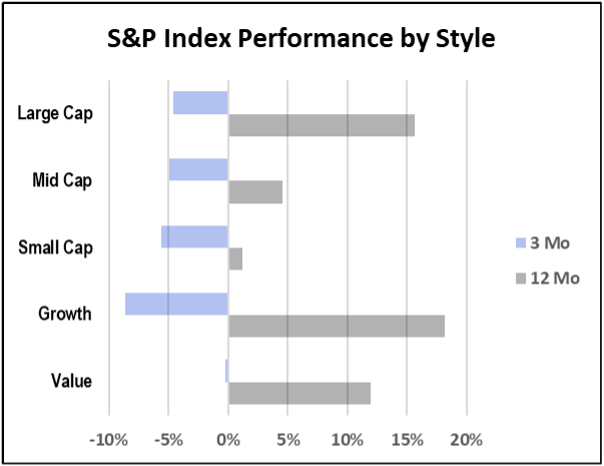

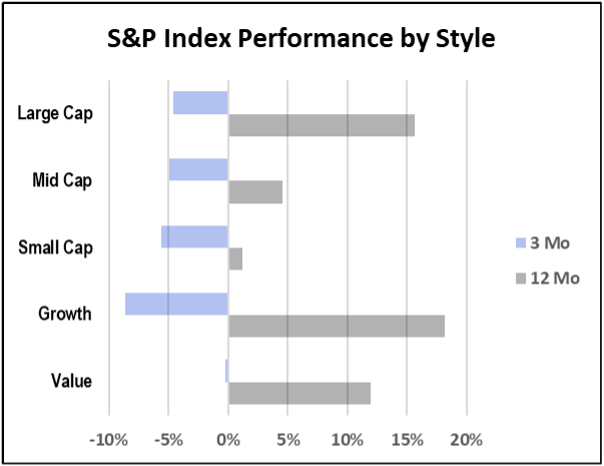

As we explained last quarter, stocks can react to inflation and interest rates in varying ways. Provided consumer incomes rise with inflation, companies can generally increase prices for their own goods and services and maintain profit margins. This makes stocks among the better inflation hedges. But faster inflation also leads to higher interest rates, as we’ve seen, and not all stocks respond to rising rates in the same way. Growth stocks, whose expected profits are mainly in the distant future, tend to suffer more as investors discount those future earnings more aggressively. Indeed, the S&P 500 growth index fell 9% in Q1 while the value index was basically flat. Overall the S&P 500 slipped 5%.

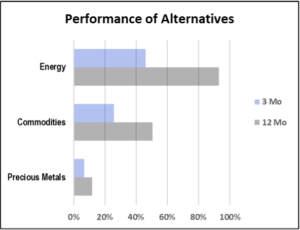

Other asset classes also suffered, making for a rather miserable start to 2022. Medium and small-sized companies fell slightly more than large ones, foreign stocks generally fell a little more than domestic ones, and the aggregate bond index fell every bit as much as stocks. Even Bitcoin lost value. Commodities offered the only haven. Oil and gas prices surged, first on rising demand from the economic recovery, then on the shock of Russia’s invasion of Ukraine. Those two countries also supply about 30% of the globe’s wheat exports, causing futures prices to spike 50% in February. Of course, no global crisis would be complete without a rise in gold prices, which are up 10% year-to-date.

All of this speaks to what has happened. As investors, what we really care to know is what happens next. Nothing will determine the future course of markets and the economy more than the global fight on inflation, which the Fed will lead, primarily by raising the federal funds rate. Increases in this rate ripple into other lending rates, like mortgages, where the prevailing 30-year rate has already risen to nearly 5% from just 3% a year ago. Higher borrowing costs raise the effective cost of those items purchased with debt, like homes and cars, but also anything that consumers might put on their credit cards. In time this negatively impacts consumer demand for goods, which ultimately eases the pressure on prices.

When we say “ultimately” we aren’t being very definite about timing and that’s for good reason. First, we don’t know how aggressively the Fed will raise rates in this cycle; second, we don’t know how quickly the market for goods will respond to those rate increases; and third, there are many markets where simply raising the cost of borrowing doesn’t dampen inflation. Gasoline and food prices are obvious examples, but so too are semiconductors, where a shortage has been key to the rising prices of computers, cars and myriad electronic gadgets. In these key examples the problem is not so much excess demand as insufficient supply, and the Fed has no toolkit for boosting the output of oil, semiconductors or wheat. The challenge for the Fed in this rate hike cycle, as in any, is to raise rates high and fast enough to tame inflation without inducing a recession. Economists call this a “soft landing.” The most recent cycle of tightening from 2016-2018 did end in a soft landing. The two cycles before that preceded the dot-com bust and the financial crisis. So the Fed’s track record is decidely mixed.

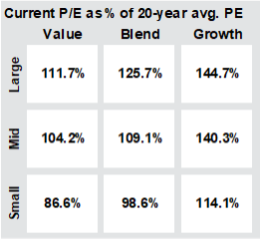

We acknowledge the near-term environment faces a great deal of uncertainty. By historical standards, stocks remain expensive and interest rates are still low. More than a few investment “gurus” point to these conditions as reason to sit this rate hike cycle out. We believe that this environment continues to present opportunities for well-diversified long-term investors. While it is true that the S&P 500 trading at 19.5 times forward earnings is historically expensive, the priciest areas of the market are concentrated in large U.S. growth companies. Relative value can still be found by tilting toward value and smaller companies. Similarly, foreign stocks markets are not so overvalued, trading at multiples equal to their 20-year averages and one-third lower than the S&P 500. Even fixed income is starting to have some allure. For the first time in several years it’s possible to construct a bond portfolio with limited interest rate and credit risk that yields more than 2%. While such a yield isn’t attractive relative to current inflation, it beats cash and the rates offered by banks on money markets and CDs.

We acknowledge the near-term environment faces a great deal of uncertainty. By historical standards, stocks remain expensive and interest rates are still low. More than a few investment “gurus” point to these conditions as reason to sit this rate hike cycle out. We believe that this environment continues to present opportunities for well-diversified long-term investors. While it is true that the S&P 500 trading at 19.5 times forward earnings is historically expensive, the priciest areas of the market are concentrated in large U.S. growth companies. Relative value can still be found by tilting toward value and smaller companies. Similarly, foreign stocks markets are not so overvalued, trading at multiples equal to their 20-year averages and one-third lower than the S&P 500. Even fixed income is starting to have some allure. For the first time in several years it’s possible to construct a bond portfolio with limited interest rate and credit risk that yields more than 2%. While such a yield isn’t attractive relative to current inflation, it beats cash and the rates offered by banks on money markets and CDs.

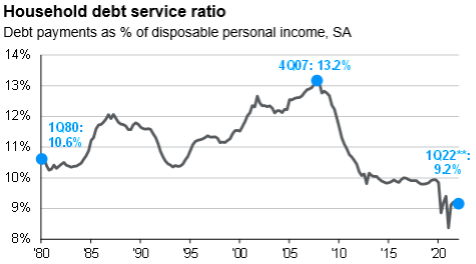

There remains a decent chance that the Fed can engineer another soft landing and avoid a recession. Afterall, we are less than two years into the current recovery and consumer finances are in good shape. Ironically, the key may be price inflation in those markets over which the Fed holds little sway. Prior to Russia’s invasion, supply chain pressures were starting to ease[1]. If that trend resumes, we could see a material slowdown in the rate of inflation over the next several months, which would allow the Fed to respond in a steady rather than frantic manner. We will be keeping an eye on oil, of course, but also semiconductors, lumber and other supply chain indices. Should our assessment of financial conditions change, we shall let you know and we will respond appropriately.

There remains a decent chance that the Fed can engineer another soft landing and avoid a recession. Afterall, we are less than two years into the current recovery and consumer finances are in good shape. Ironically, the key may be price inflation in those markets over which the Fed holds little sway. Prior to Russia’s invasion, supply chain pressures were starting to ease[1]. If that trend resumes, we could see a material slowdown in the rate of inflation over the next several months, which would allow the Fed to respond in a steady rather than frantic manner. We will be keeping an eye on oil, of course, but also semiconductors, lumber and other supply chain indices. Should our assessment of financial conditions change, we shall let you know and we will respond appropriately.

[1] Per the Federal Reserve Bank of New York Global Supply Chain Pressure Index.