26 Dec A Good Year for Investing (Only)

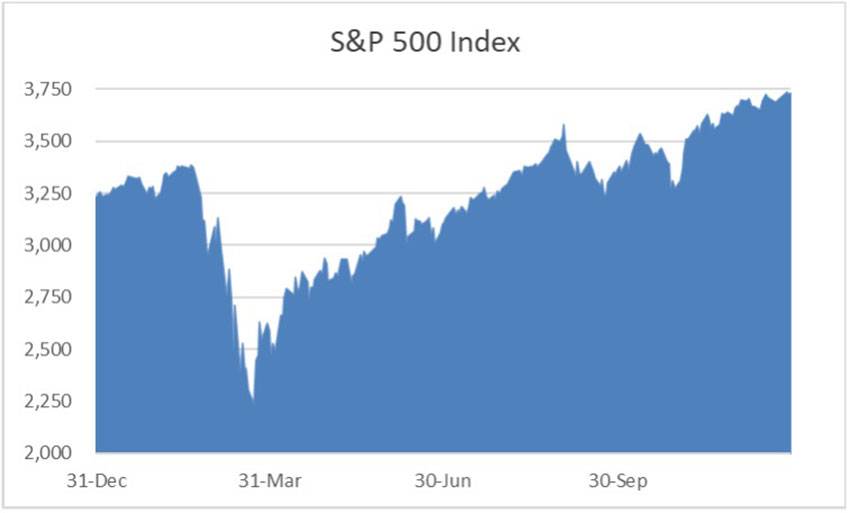

Much has been written about the terrible, horrible, no good, very bad 2020. And so it was – for humans. For investments, on the other hand, 2020 was a fine year. After the financial shock of the pandemic wore off, stock markets skyrocketed. The S&P 500 shot up 67% from its March low to finish more than 15% higher than a year ago. The combination of massive global fiscal and monetary stimulus gave consumers discretionary money to spend while lowering interest rates to all-time lows. Other asset classes sensitive to interest rates, like bonds and precious metals, rallied as well.

Investors in financial markets displayed considerable resilience in looking past the miserable conditions of the present to anticipate brighter days ahead. The extraordinarily rapid development of COVID vaccines promises to eventually fulfill those hopes. People widely believe the new year will bring a gradual return to normalcy accompanied by a steadily growing economy. It’s not surprising that investors feel optimistic. But just as 2020 proved that bull markets don’t require improving economic conditions, 2021 has the potential to show that better economic conditions don’t always lead to bull markets. What really matters is whether company profits meet expectations, and right now expectations seem ambitious. Consensus analyst estimates call for corporate earnings in 2021 to jump almost 25%, which would exceed 2019 levels. Yet we begin the year with nearly twice as many people unemployed.

There are other warning signs. The height of the stock market’s peak is more impressive than its breadth. Nearly 60% of last year’s gains came from technology stocks, a sector that represents just 6% of GDP and 2% of jobs. A multi-year trend continued of investors favoring growth stocks – representing companies whose share prices reflect lofty expectations for future earnings growth – over their value counterparts. The price-to-earnings ratio for growth stocks is now nearly 2 times the 20-year average. Value stocks are only slightly more expensive than historical averages. While low interest rates can explain some of the relative expensiveness of stocks in general and growth stocks in particular, expensive valuations have been accompanied by worrisome investor behaviors last seen in the 1990’s. Last year individual retail investors opened more than 10 million brokerage accounts, an all-time record. Many of these were opened on platforms like Robinhood, which uses gimmicks intended to make stock trading more addictive. Unsurprisingly, the share of daily trading activity represented by retail investors doubled from 10% to 20%. Investments made with borrowed money (margin) jumped 28% last year, to an all-time record. A recent story in the Wall Street Journal even featured an individual who sold his house to buy more stock in Tesla.

There are other warning signs. The height of the stock market’s peak is more impressive than its breadth. Nearly 60% of last year’s gains came from technology stocks, a sector that represents just 6% of GDP and 2% of jobs. A multi-year trend continued of investors favoring growth stocks – representing companies whose share prices reflect lofty expectations for future earnings growth – over their value counterparts. The price-to-earnings ratio for growth stocks is now nearly 2 times the 20-year average. Value stocks are only slightly more expensive than historical averages. While low interest rates can explain some of the relative expensiveness of stocks in general and growth stocks in particular, expensive valuations have been accompanied by worrisome investor behaviors last seen in the 1990’s. Last year individual retail investors opened more than 10 million brokerage accounts, an all-time record. Many of these were opened on platforms like Robinhood, which uses gimmicks intended to make stock trading more addictive. Unsurprisingly, the share of daily trading activity represented by retail investors doubled from 10% to 20%. Investments made with borrowed money (margin) jumped 28% last year, to an all-time record. A recent story in the Wall Street Journal even featured an individual who sold his house to buy more stock in Tesla.

Valuations are not generally as bubbly as in the 1990’s, but for some growth stocks, they are perilously close. The market value of Tesla now exceeds that of the next largest 7 automakers combined, despite losing money on the relatively few cars it makes. It is but one example of froth in the super-charged electric vehicle industry. Other examples of small, virtually profitless but exceedingly valuable companies can be found in cloud computing (e.g., Zoom). The earlier successes of companies like Amazon and Microsoft have seemingly paved the way for the current upstarts. Some of these may become the next generation of truly great companies. But the price you pay matters. An author of this newletter had the unhappy experience of buying Microsoft in the late 90’s, avoiding at least the profitless and doomed darlings of the day like AOL and Netscape. Microsoft stock went up for a couple of years but, like the rest of the market, plummeted in the dot com crash of 2000. Over the years Microsoft grew into a behemoth – revenues increased 10% annually from $22 billion in 2000 to $93 billion in 2015 – but its stock remained under water for more than 15 years. More reasonably priced value stocks fell less sharply and reached new highs in a fraction of the time.

When certain stocks soar like they have of late, individuals are prone to fear missing out on potential riches. They look at what has been doing well and convince themselves that this performance will continue into the future (a phenomenom known as recency bias). Short-term success leads to overconfidence which in turn leads to excessive risk-taking (concentrated positions, frequent trading, margin loans). These are behaviors that are oftentimes associated with stock market tops, and ones that we would caution against. If history is about to rhyme, these investors may be running out of time.

As we begin this new year, we wish all of our readers good health and happiness, and hope that the days ahead are brighter than the ones behind.